I can’t believe it’s been just over a year since the poet John Foggin died. It came up on my Facebook memories a few days ago. Since then, I’ve been re-reading some of his many collections, straining my ears to hear his voice again in those poems, and feel some of the joy that poured out of him when he got excited about a poem or a poet.

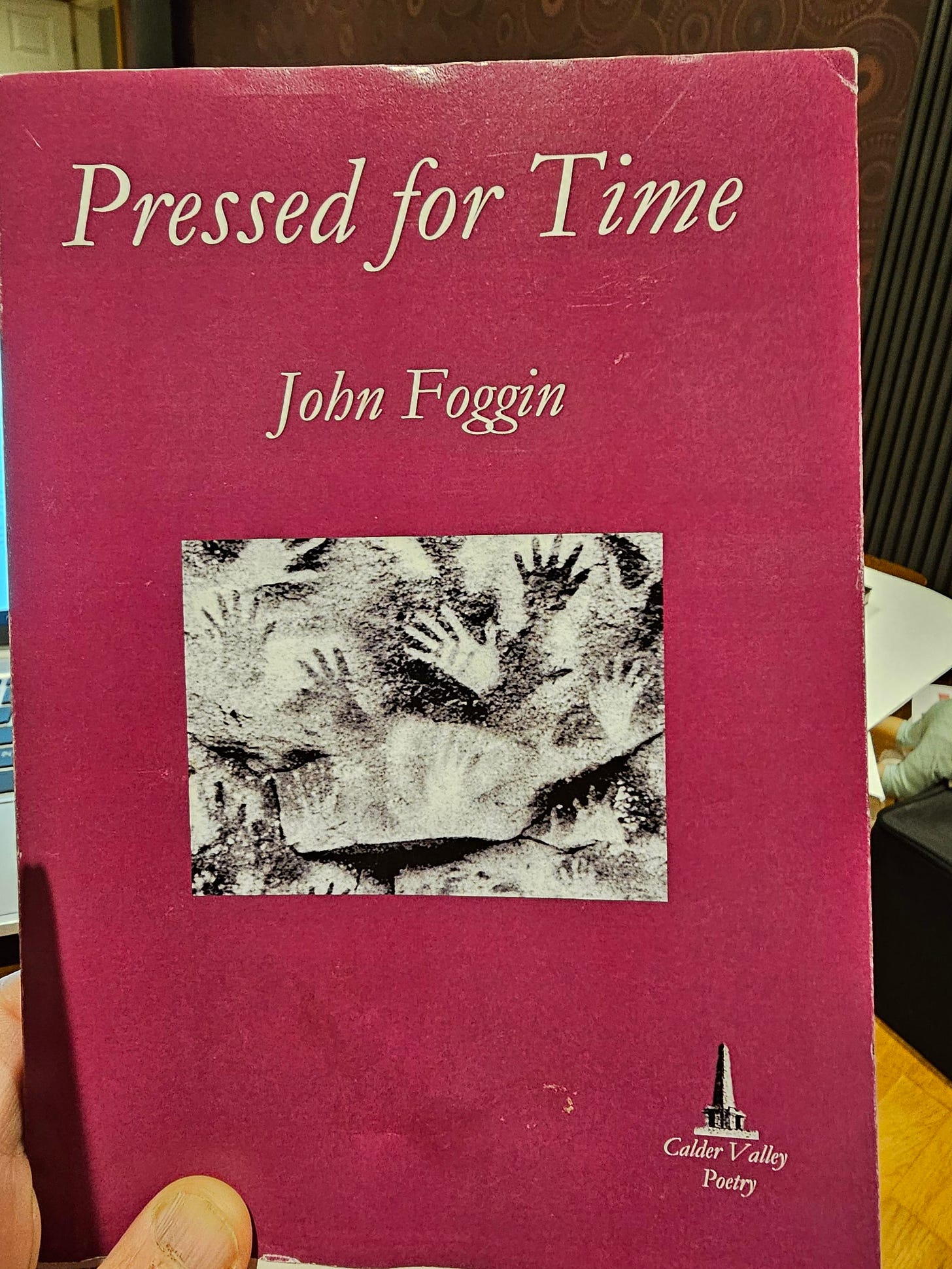

His last collection, published a few months before he died is called Pressed For Time, published by Calder Valley Poetry.

The first poem is A Commission to Paint the Butcher. It is a wonderful poem to start a collection with - and it’s John all over. He cycles through a few hundred years of art history in the space of a poem, teaching me something on the way, but doing it so lightly, so artfully. In fact, it is almost as if he is teaching himself, reminding himself what he knows, which is not just the style of Beryl Cook or the Old Masters, but about perception. That it matters how we look at things, how we look at art, how we look at people. And following on from that, it matters how we then represent them. So this poem, ostensibly about painting becomes about perception, about our responsibility as artists, as makers in the world. Perhaps it is about the way that art (and by art, I mean any artform) can change the world because it changes the way we see the world.

Here is the poem, with grateful thanks to Bob Horne, his editor at Calder Valley Press.

A Commission to Paint the Butcher Beryl Cook would give him a straw boater and a red face, and there'd be sausages. What should he be doing, the butcher? Splitting a carcase? Cutting chops and collops? Boning out a whole pig's head? Stanley Spencer would give you the blues of bone, the green tinge of flesh. That would be good, the structure, the ears, the solid textured flesh, and the absence of blood, the pig all drained and scrubbed and pale, an is that the best you can do? sneer. The Old Masters would give him artful gloom. (A headless carcase hanging just off-centre.) (The boning-knife's slim slice of blue.) You'd need the light to fall on the planes of the skull, the dark of the big nostril, its trickle of black; the shine of bottle-crunching teeth, the ragged collar of the neck. Peter Blake for the blue-and-white striped apron with brown stains round the middle; white rubber boots, a wall of white glazed tile.

You can order a copy of Pressed For Time, direct from the publisher Calder Valley Press

Reading John’s poems again, I’m struck by this sense of urgency in some of his work, as if the words were pouring out of him, and those of us who sat next to him in a workshop would say, well they did. They did pour out of him, in beautiful handwriting. In Mother, you can hear that urgency in the way that first sentence is an address to the ‘you’, how it unrolls itself, and corrects itself. The fireweed roots itself not just here, or here, but everywhere. Look at how he follows this with a factual, shorter sentence. Then the third sentence is again an address. It starts ‘How you clung’ and continues with the pattern of the ‘how’. This sentence says to the fireweed, who is also the mother, I see you. I notice what you are. I see your nature. And then a final two shorter sentences to finish the poem off, and these two lines teach us about grief, and love. That when we love and have loved, everything reminds us of those we have lost.

MOTHER

JOHN FOGGIN

You were fireweed that roots itself in poor soil,

in the footings of abandoned mills, old workings,

in raked yards of furnace slag. Seed blown

on the fume of banked hearths, in ashpit dust.

How you clung to any crack and crevice,

put out your plumes and spires of lavender,

rose-pink, year after year, how your head

grew white, how your soft hair blew but not a thing

could root you out, not frost, not fire,

nor the veilings of industrious spiders.

You sent yourself out on the wind.

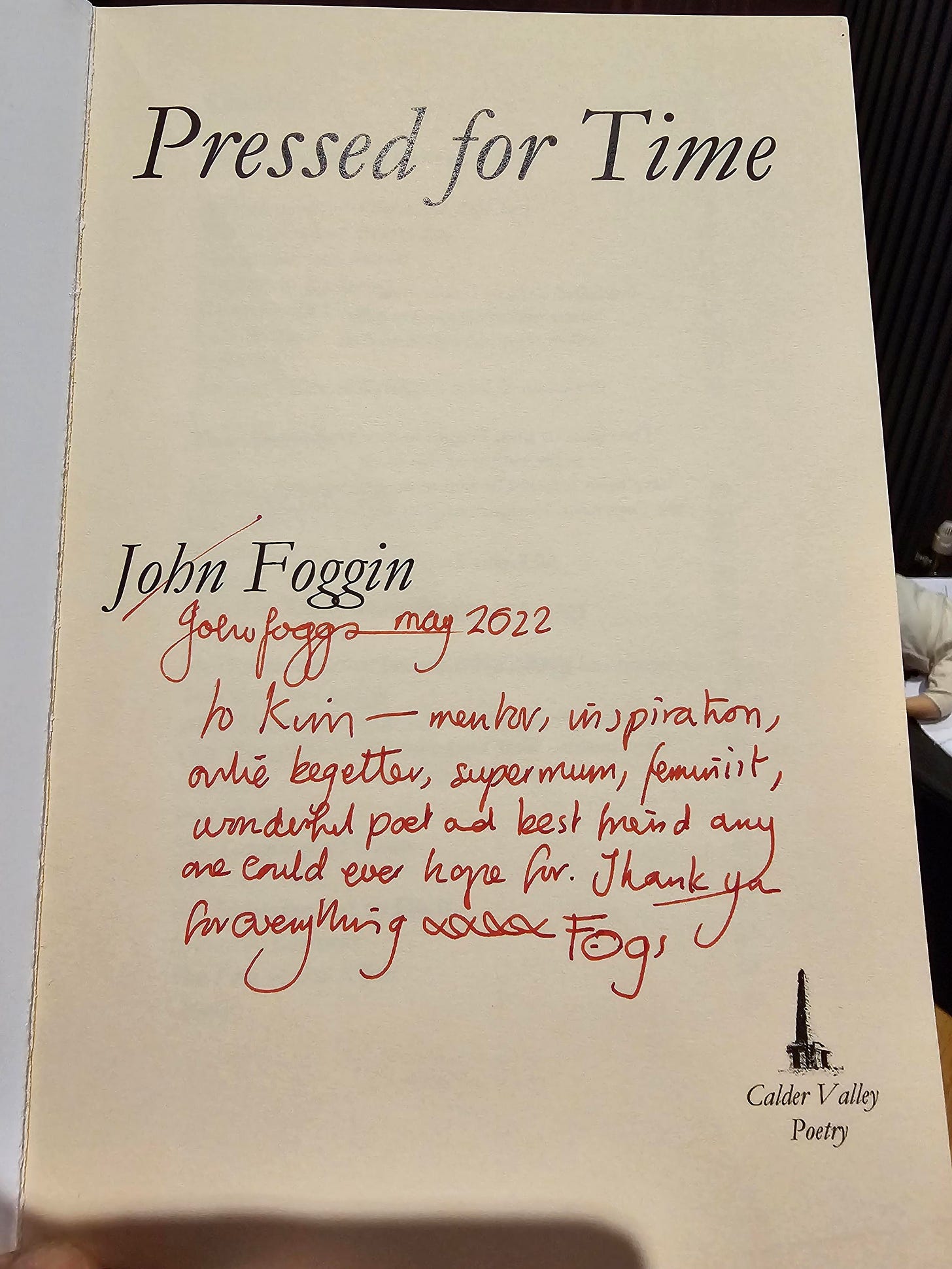

You blow everywhere. John sent me a copy of his book, as he did with all his books and his pamphlets. Every one has a note inside. I read them now and I don’t recognise myself, or the self that John saw. That was another of his great gifts of course - not just his poetry, but the way he ‘saw’ people. The way he saw me made me want to be worthy of his seeing.

Here is his beautiful handwriting, looping across the page. John said things like this because he meant them, for no other reason than he wanted to. I miss him terribly, and will probably miss him more over the next couple of weeks, as I embark on teaching a few residential courses. I’m off to Garsdale in a week or so, and I plan to go for a run on the moor, and read one of John’s poems to the wind, and the sky, and the heather, and if I can find some sheep to listen, I will include them too.

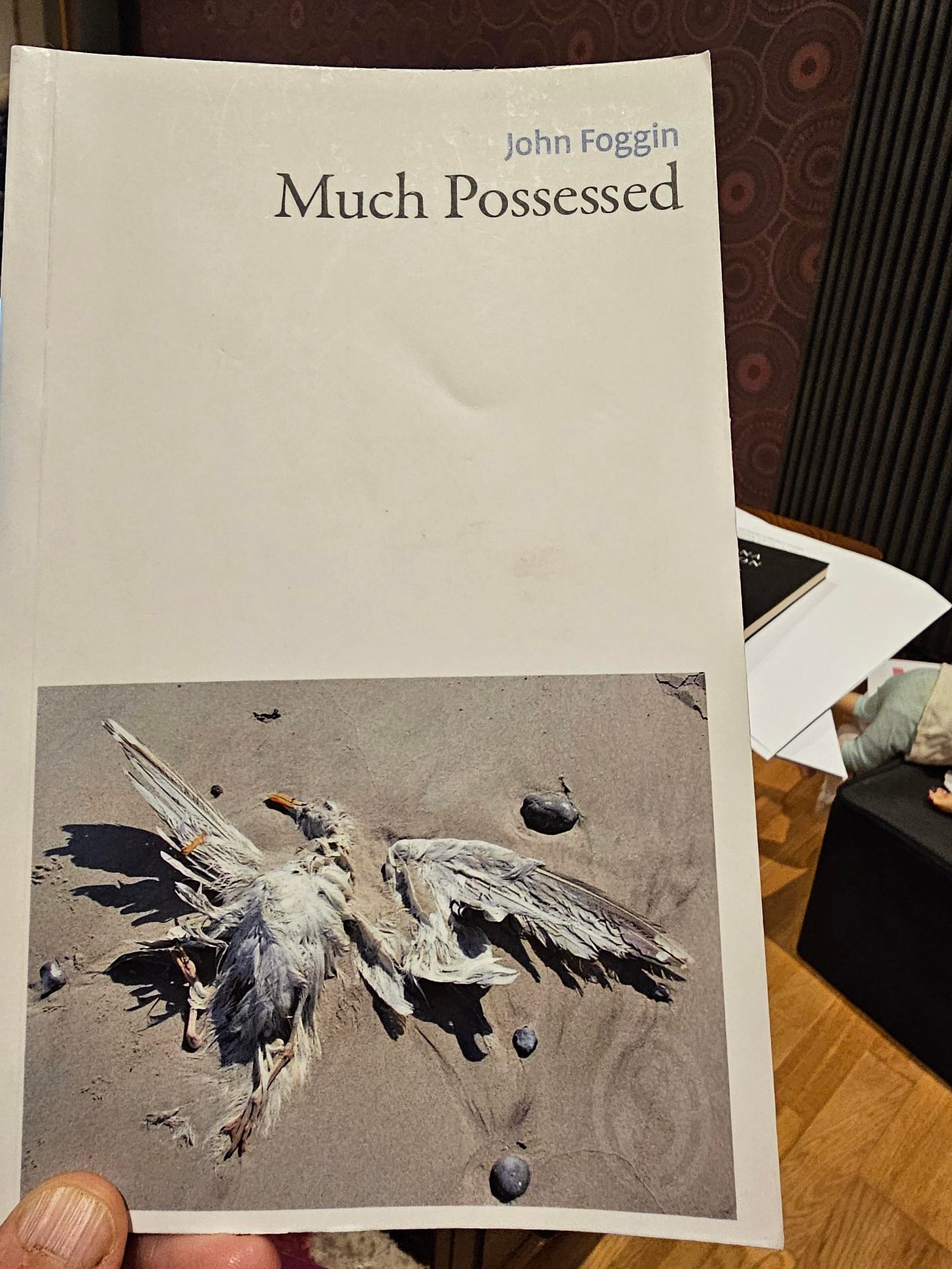

I wanted to finish with In the Meantime. This poem was published in John’s first full-length collection Much Possessed (Smith/Doorstop, 2016). It was John’s dream to win the Poetry Business pamphlet competition, and to have a book published by Smith/Doorstop.

I love that this poem reappears again as an epilogue in Pressed For Time. Perhaps John wanted to complete that loop between that first book that meant so much to him, and his editors, Ann and Peter Sansom, and his last book, edited by his friend and publisher Bob Horne.

Perhaps one day someone will write about the ordering of collections, and use this as an example. In Much Possessed, this poem sits in the middle of the collection. You can still tell it’s a fine poem there. It sits before the title poem of the collection and in a general grouping of poems about birds. But moving it to the end of Pressed for Time feels to me like a stroke of genius. By placing it at the end, it speaks to me about death, about what comes after, about hope, about life, about not-knowing. It holds the curiosity that perhaps needs to burn inside all writers to enable us to write, so that we can use writing as a way of finding out what we know, or perhaps even what we don’t know, or what we don’t know that we know. The poem takes on so much weight as the final poem - but it holds underneath that weight, that epiphany, without so much as a tremble. And of course, it feels like he’s talking to us, the people left behind, telling us not to worry, because, after all, who does know what happens next?

IN THE MEANTIME

JOHN FOGGIN

because that's how it is, the sparrow

flying into the mead hall, bewildered

by smoke-reek, gusts of beer-breath,

out of the wild dark and into the half-

light of embers, sweat, the steam

of fermenting rushes, and maybe

a harp and an epic that means nothing

in a language it doesn't know, this sparrow,

frantic to be out there, and maybe

it perches on a tarry roof beam, catches

a wingtip, comes up against thatch

like a moth on a curtain, and it beats

its wings, it beats its wings, it tastes

a wind with the scent of rain, the thin

smell of snow, of stars, and somehow

it's out into the turbulence of everywhere,

and who knows what happens next.

Brilliant thank you, wonderful poems. Only the other night at zoom, a poet reminded me of John's voice, and being the age I am, I couldn't remember John's surname. So thank you for that too.

A beautiful remembering and tribute to Fogs.