First Draft to Last Draft

The poem that arrives as a gift

Content warning: discussion of domestic violence in this post

Until this night, I believed that there were, broadly speaking, two types of poems, in terms of what it took to write them.

The first type is the usual type - the ones that arrive through hard work, that come because you show up at the writing desk. Imagine a huge rock that you have cut from a mountain, a rock that you cut because in certain lights, you think you can almost see a seam of precious metal running through, or the shape of an animal or a person - a rock that you could carve into something else. One of the tools that you use for the carving is time, of course. And the second is the space to sink into the landscape of the self and listen.

The second type of poem is the poem as gift. It arrives from nowhere and needs little editing, perhaps the removal of a full stop, or a comma or two. It has mystery at the heart of it. If it comes from you at all, it comes from a part of you that you don’t know, to tell you something that perhaps you need to hear, or that you didn’t know you knew. I believed that you don’t get many gift poems - maybe one or two a book if you’re lucky.

One of the poems that I have always thought of as a gift poem is “In That Year” from my first collection The Art of Falling (Seren, 2015). What I remember about writing this poem is that I was writing late at night in the living room, after my husband had gone to bed. Back then, before I had my daughter, writing late at night was part of my routine. My favourite place to write was a cushion on the floor next to an electric heater, and then I created a kind of nest from books and papers that I was reading or working on. That night, I was tired, and I ended up falling asleep on the floor, whilst I was writing. I woke up with my head in the dog basket, and “In That Year” in my notebook.

“In That Year” is the first poem in a 17 poem sequence about domestic violence. It functions for me almost as a seed poem from which other poems in the sequence spring from.

When I decided to write about the drafting process, I thought it would be interesting to write about this poem, and that it would also be useful to find the original notebook to compare the first draft with the final, published version. I expected to have two pretty much identical versions - one handwritten and one typed. What I found in my notebook was much more interesting than that.

Here is the final, published version of “In That Year”.

IN THAT YEAR And in that year my body was a pillar of smoke and even his hands could not hold me. And in that year my mind was an empty table and he laid his thoughts down like dishes of plenty. And in that year my heart was the old monument, the folly, and no use could be found for it. And in that year my tongue spoke the language of insects and not even my father knew me. And in that year I waited for the horses but they only shifted their feet in the darkness. And in that year I imagined a vain thing; I believed that the world would come for me. And in that year I gave up on all the things I was promised and left myself to sadness. And then that year lay down like a path and I walked it, I walked it, I walk it.

One of the seeds in this poem was the phrase ‘the language of insects’. I did not know what I meant by this phrase. I had to write a poem to find out, and this became one of the poems that comes later in the sequence. It begins “This is the language of insects, this body / low to the ground, this single purpose, / this living with dirt, this stop-start-stop…” I was trying to write about the physical violence exacted on the body when you live in a house where violence also lives. The acts of daily submission which keep your body low to the ground, and leave you feeling grubby, as if you are living with dirt on your skin.

In my notebook, the first draft of “In That Year”. The draft covers two pages, and it’s not until I’m typing it up that I realise this is actually two drafts. There are different lessons for me to learn from both of these drafts, which I am going to try and articulate in the hope they will be useful both for myself in future, but perhaps also for other people.

What is clear though is that this poem was not quite a gift in the sense that I was thinking of it. There was an editing process - it didn’t come all in one go. I created a legend around it, a mythology around this poem. It was a gift, but not a gift in the way that I thought it was. Now I look back and realise it wasn’t the poem coming in one go that was a gift. It was the images. The images were gifts that came fully formed into my mind. They had meaning in and of themselves before I knew what it was.

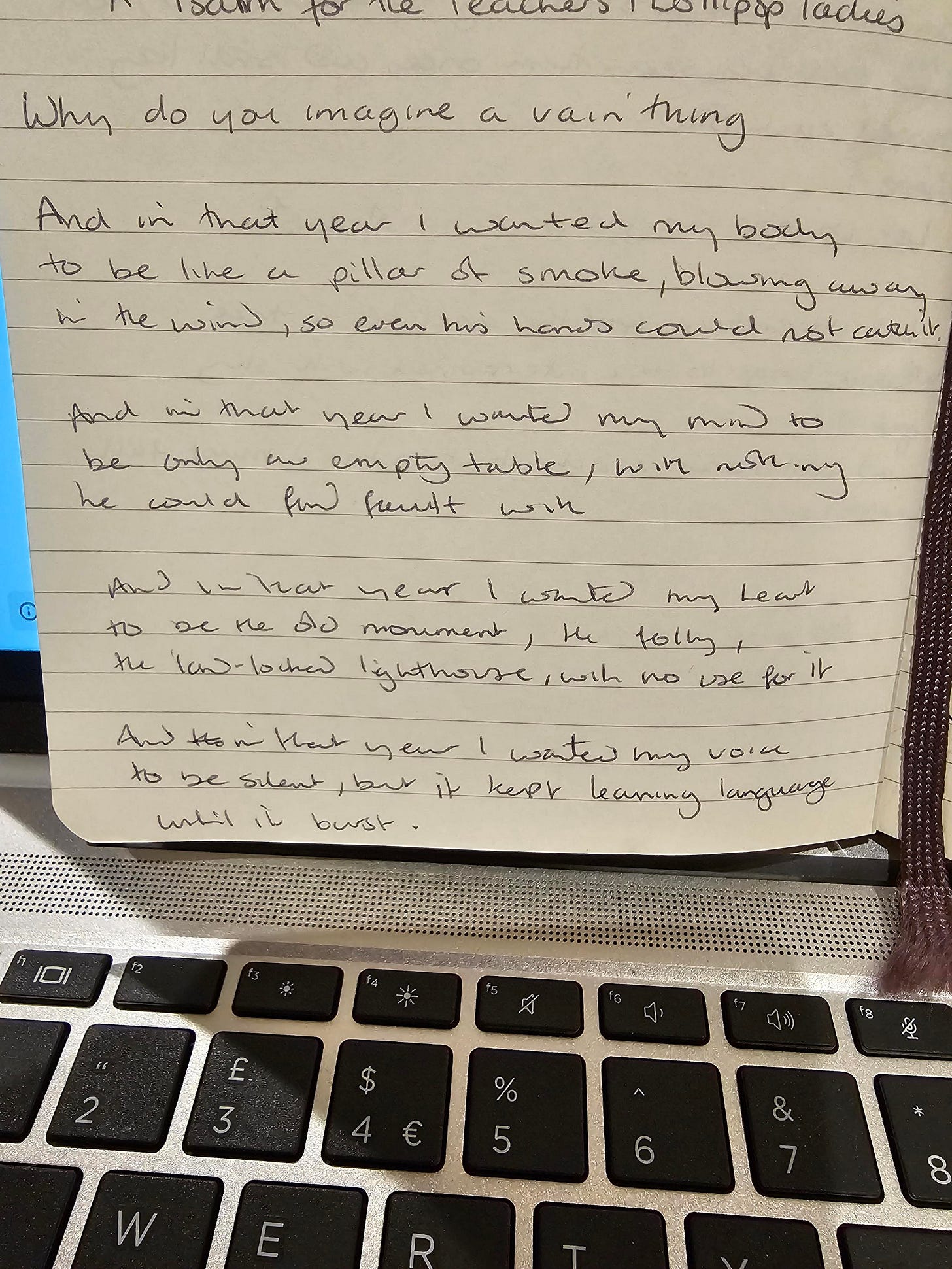

Here are the pages of my notebook containing the first draft of “In That Year”.

Draft 1:

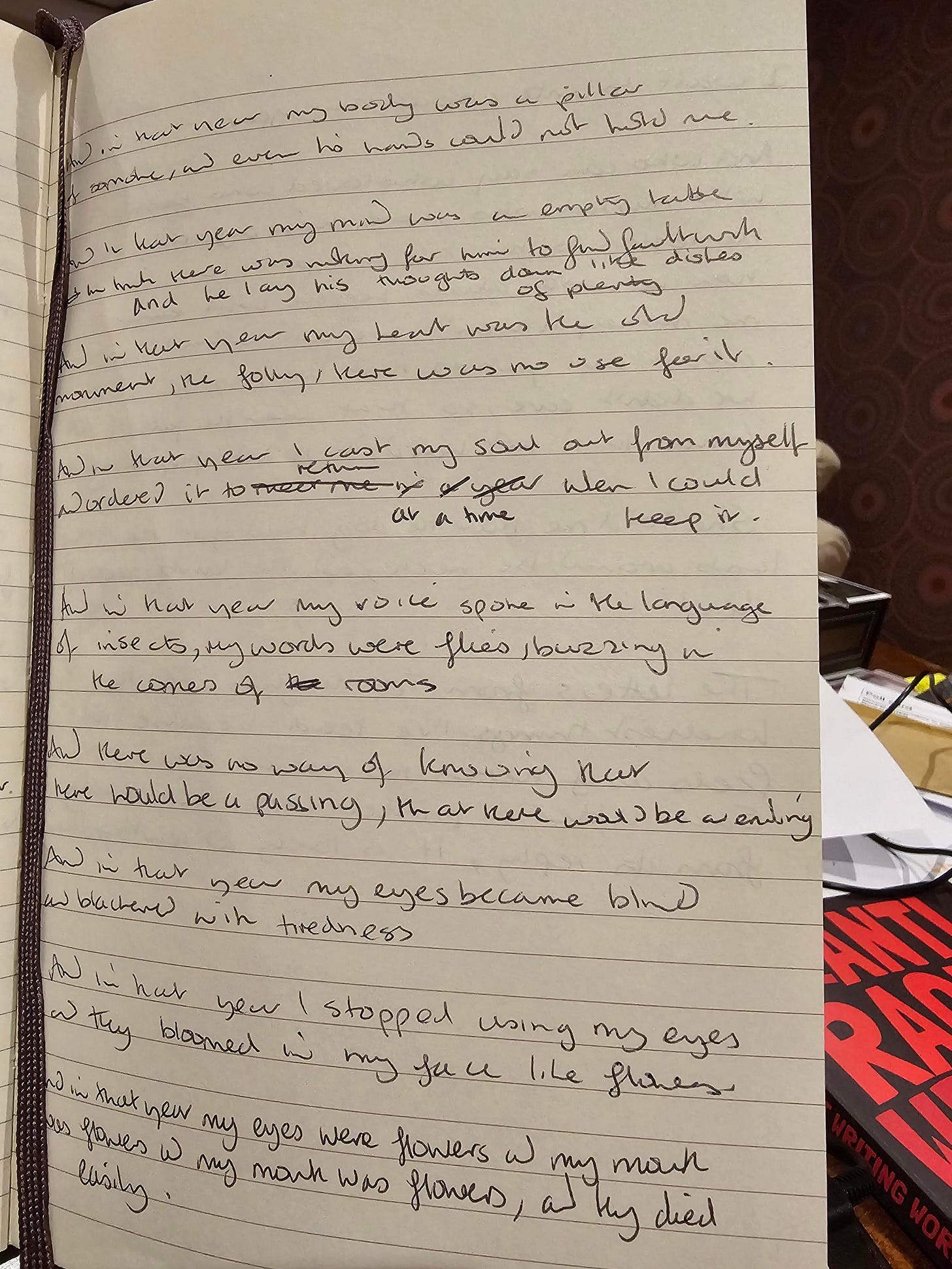

Draft 2

Draft 1

Why do you imagine a vain thing And in that year I wanted my body to be like a pillar of smoke, blowing away in the wind, so even his hands could not catch it. And in that year I wanted my mind to be only an empty table, with nothing he could find fault with. And in that year I wanted my heart to be the old monument, the folly the land-locked lighthouse, with no use for it And in that year I wanted my voice to be silent, but it kept learning language until it burst.

When I read this back now, those images are like seams of gold shining from behind the language that is getting in their way. The body as a “pillar of smoke”. The mind as an “empty table”. The heart as the “old monument, the folly.” The question of the title “Why do you imagine a vain thing” which became a statement in the final line “I imagined a vain thing”. When I wrote the title, I didn’t know the vain thing I was imagining. It took writing the poem to learn this. And that refrain “And in that year” - that was another gift - the song of that phrase. The rhythm of it.

By draft 2, I am starting to understand why it felt like a gift. The first three couplets pretty much slot into place, almost the same as the final version of the poem. It’s draft 2 that I nail another image down ‘the language of insects’ which I will need to write another poem to fully understand.

Draft 2

And in that year my body was a pillar of smoke, and even his hands could not hold me. And in that year my mind was an empty table and there was nothing for him to find fault with. And he lay his thoughts down like dishes of plenty. And in that year my heart was the old monument, the folly, there was no use for it. And in that year I cast my soul out from myself and ordered it to return at a time when I could keep it. And in that year my voice spoke in the language of insects, my words were flies, buzzing in the corners of rooms. And there was no way of knowing that there would be a passing, that there would be an ending. And in that year my eyes became blind and blackened with tiredness. And in that year I stopped using my eyes and they bloomed in my face like flowers. And in that year my eyes were flowers and my mouth was flowers and my mouth was flowers, and they died easily.

The rest of this draft on first reading, seems like a write off. The couplet about ending and passing doesn’t exist any more - and all the stuff about eyes - also has been edited out.

However - this section illustrates why I have always thought of this poem as a seed poem. Although now I write that, I don’t think the image quite works. This poem is a well that felt deep enough for me to draw from. Why was I going on about eyes at the end? Well, later on in the sequence, there is a poem called “On Eyes” where I mixed facts about eyes, with facts about black eyes. And running the risk of oversharing, but the moment when I was punched in the eye, was the moment I finally realised that none of what was happening to me was my fault.

The lines about eyes in this draft are not right. The first couplet, where the eyes are ‘blind and blackened with tiredness’ are hyperbole and not specific enough. The next couplet again talks about not using eyes but the image of them blooming in the face like flowers is just frankly too odd - although I think what I was trying to really pin down there was the blooming of pain, perhaps. And the final couplet I just lose control of image and language and everything spills out everywhere - and this loss of control is what shows that there is another poem in here, that there is something important that I want to say here.

So eyes - and being able to truly see what is happening, and that seeing in itself happening through a lens of violence was, is an important part of my story. It was the turning point where everything changed, everything transformed. But again, I had to write a poem to understand all of this. But even before I wrote the poem, I had to edit the eyes out of this poem.

So what are the lessons? For this poem, and this draft - lesson 1 - the images were the gifts. That’s what made me feel as if this poem came easily - because those images fell into my conscious from somewhere else. Lesson 2: listen to your first drafts because there might be other poems lurking in there, waiting to be written.

Lesson 3: as a teacher and mentor, I am working more and more around the art of conversations around poems. If this was a poem by a mentee or student, I hope I would ask the question - why are you writing about eyes? What is the significance of eyes to you? What are you trying to say that you are not saying yet?

Thank you for reading this First Draft to Last Draft post - I’m planning on doing another, mostly because I’ve enjoyed doing it and I’ve been surprised by what I’ve found out on the way. The next one will be for paid subscribers - not because I want to keep anybody out, but because I would like to give something extra to those people who have been supporting us with subscriptions.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, you might enjoy a book of interviews with poets about their drafting process called The Process of Poetry, edited by Rosanna McGlone. Full disclosure - I’m in it, but it has some fascinating interviews with the likes of Don Paterson, Pascale Petit etc.

If you would like to buy a copy of The Art of Falling, where you can find “In That Year” along with the other 16 poems in the sequence around domestic violence, you can buy a signed copy from my website here.

The more I talk to poets, the more I feel that these poems, the ones that are in essence written by the realisation our voice demands to be heard regardless of the emotional response, are also the ones that build emotional resilience.

Looking back at pieces in the last two years which I would consider gifts, it was the images and where they sent me back to, how they made me feel about the story they told that made me accept that what mattered had finally lost its emotional power.

I can also accept that I struggle to have that clarity when emotion supersedes my ability to rationalise it. Only by dealing with how my heart lives within those moments does it become possible to sublimate their history into a response.

Thank you for breaking your process open so we can see the emotional resilience that created them ❤️❤️❤️

Thank you so much for this, Kim!! It’s absolutely the best way to “learn” from another poet. I also love your take on what the gift is, and how it works in crafting a poem. I look forward to other “deconstructions” and think whatever poem calls to you will be the best one for us to learn from. x