If I had to name all the reasons I write, then “to look at the things I don’t see” would be near the top of that very long list.

Over the last 8 days, I’ve been working with the nature writer Miriam Darlington – she of ‘Owl Sense’ and ‘Otter Country’, ‘10 poems from the Coast’ and the Times Nature Notebook. Together, we’ve been co-hosting “30 Days Wild Writing” daily nature writing workshops, which take place live online at 9am and which are also available as recordings.

It's the first time we’ve tried this – and though I’m used to the rigours (and considerable joys) of delivering a writing hour with Kim throughout January, a series of themed workshops is a very different kettle of fish/ birds/ badgers/ tardigrades. January’s workshop demand a good overview of the poetry published in the previous year; Wild Writing requires familiarity with of moss species, the anatomy of earthworms, the remarkable resilience of nematodes, folklore, herbal remedies, the history of land rights … as well as a decent knowledge of the poetry, prose and fiction in which they appear. Needless to say, it’s challenging …. demanding, exhausting, educative and incredibly rewarding.

As is working with a new co-host. Miriam is knowledgeable, anarchic, funny – a ball of passionate energy. But of course, I miss Kim. It’s more than ten years since I first ran a course with her, and since then, we’ve worked together in residential settings across the country, we’ve co-directed a festival, co-authored poetry and articles, critiqued each other’s work, attended readings together, danced, sang karaoke and got drunk and miserable and wildly enthusiastic together, and honed the art of delivering workshops together so finely, we’re like tennis doubles. Which is to say, I know without looking where Kim’s balls are.

And so to the poetry. Here, in words, is a version of a workshop which I delivered in our Wild Writing Week 1:

Soil: The World at your Feet.

Warm up:

At the top of your page, write “Soil Is”.

Then for two minutes, write a list of everything that soil means to you. You can be literal, scientific, poetic, personal, humorous, anecdotal.

Then consider these incredible facts:

- 1 teaspoon of soil has more organisms in it than there are people on earth.

- Six inches of soil feeds eight billion people

- Soil holds 3 times the amount of carbon found in the atmosphere.

- It takes at least 500 years to form one inch of topsoil

No wonder then, in his natural history of soil “Dirt: the ecstatic skin of the earth”, William Bryant Logan asks “How can I stand on the ground every day and not feel its power? How can I live my life stepping on this stuff and not wonder at it?”

Exercise 1: Feel the power!

For seven minutes, write about an encounter with soil or dirt in which you were reminded of its power. This encounter could be ecstatic, educative, emotion, painful - watching seeds grow, for example, or a painful face-plant on a muddy path.

You might want to share your writing on Soil Voices, who aim to fill their interactive map with soil stories from across the UK

Next, consider Soil by George Szirtes

It’s a perfectly observed, achingly painful poem, which manages to simultaneously capture the particular and the unknowable. Perhaps the poem is given even more resonance when you know that George Szirtes was born in Hungary, to Jewish parents who survived concentration and labour camps - and in 1956, George, his brother and his parents were forced to flee Hungary and seek refuge in the UK. Soil is at the core of the poem, standing in for a sense of home – and like language, it’s an unpredictable, organic material. George shapes the poem with his trademark exquisite skill and with a light touch which leaves the language space to breathe, to do its own work.

Exercise: The soil of home:

Like George Szirtes, describe your home soil: its precise colour and weight; the smell of it; how it feels in your hand. Allow the language to have its own life; let the words grow in whatever direction they want.

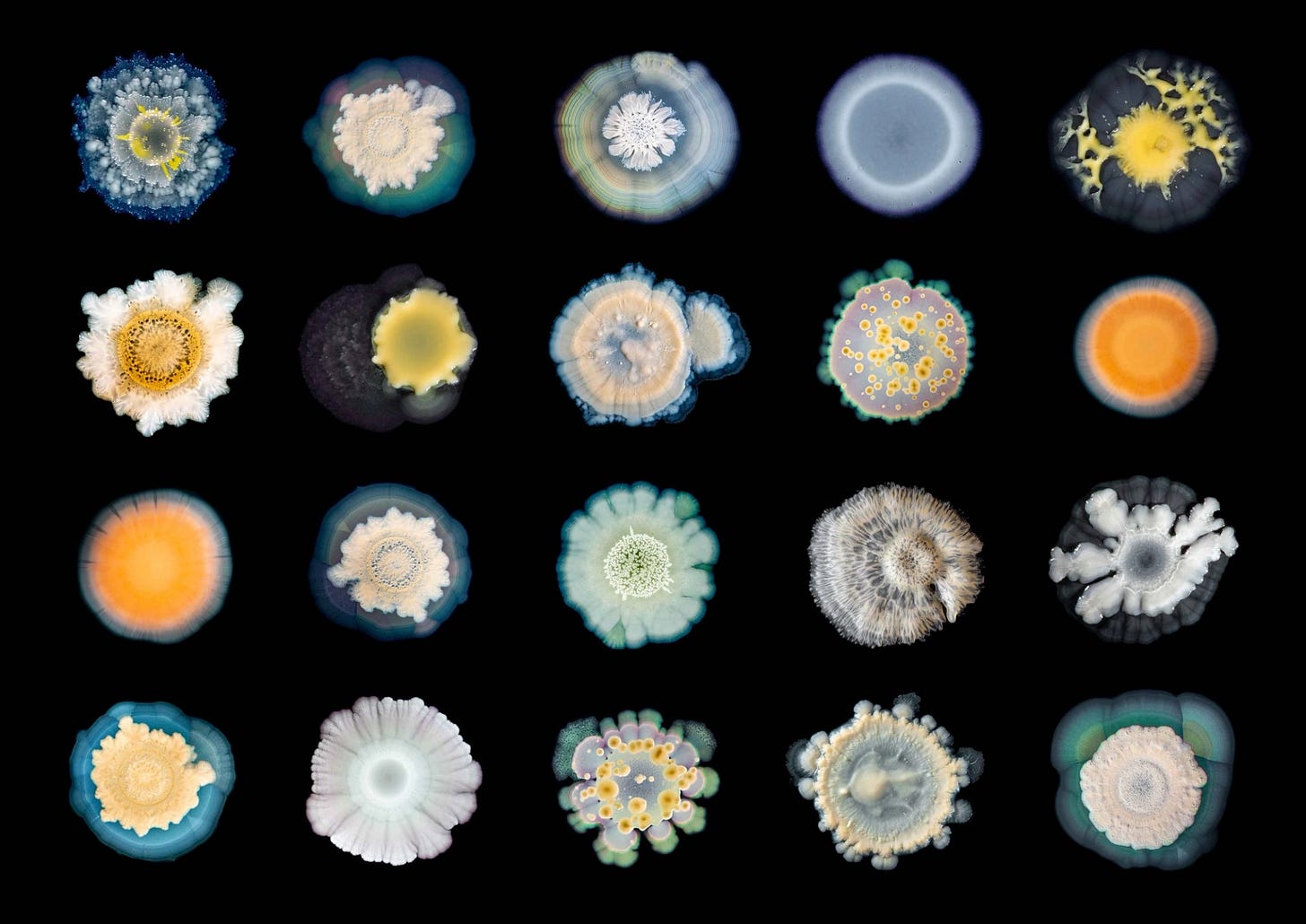

Now consider that as well as being our homes, our soils are also home to the greatest collection of microbial diversity on Earth. This includes bacteria, algae, and archaea, protozoa, fungi as well as billions of tiny creatures like nematodes, rotiphers and tardigrades - and only about 1% of the microorganisms found in soil have been identified! Yet, because we cannot see them, the life of our soils goes unacknowledged and unprotected, and every year, 12 million hectares of agricultural soil are lost to severe soil degradation, leaving some soils in a state of desertification.

Art and poetry, like soil, is a wild thing, a place of organic growth – but it is also a scientific instrument. When we put things in a gallery, in a poem, we place them under a microscope … we make the invisible visible. In the recent “SOIL: the world at your feet” exhibition at Somerset House, Jo Pearl’s Oddkin used ceramic mobiles to made visible microbial life forms which exist in their billions in every spoonful of soil. This act of making visible the invisible seems to me to be one of art’s superpowers.

Exercise 3: for 7 minutes, write in response to this title “For everything that is overlooked until you look very hard”.

Finally, whilst we might acknowledge soil’s beauty and fascination in poetry and creative writing, it can also be contested, fought over. It can be site of horror, a witness to terrible atrocities: the mud of the Somme; the slave villages unrecorded on maps and present in shards and organic traces; the mass graves and slaughter.

What a Gazan should do during an Israeli air strike

Turn off the lights in every room / sit in the inner hallway of the house / away from the windows / stay away from the stove / stop thinking about making black tea / have a bottle of water nearby / big enough to cool down / children’s fear / get a child’s kindergarten backpack and stuff / tiny toys and whatever amount of money there is / and the ID cards / and photos of late grandparents, aunts, or uncles / and the grandparents’ wedding invitation that’s been kept for a long time / and if you are a farmer, you should put some strawberry seeds / in one pocket / and some soil from / the balcony flowerpot in the other / and hold on tight / to whatever number there was / on the cake / from the last birthday.

And it can be witness to acts of kindness, as in Naomi Shihab Nye’s famous Gate A-4 For your final exercise, write for ten minutes about “What has the soil seen”. Let your language be alive; let it find its own way. The earth is witness to horror, and also to life and hope. If you feel able, then allow your language to hold the pain, but in Naomi’s words, in seeds which continue to grow, in the diversity of life forms flourishing beneath your feet, remind yourself that Not everything is lost.

If you’d like to join Writing Hours, you can sign up via this link: Wild Writing. Monthly and weekly tickets are available, and you can also sign up for a single day.

A Diversity of Forms, by Tim Cockerill.

Clare and Miriam's Wild Writing course is one of the best things I've done for myself this year. I’ve found myself exploring creative paths I didn’t know existed, getting to know myself better and connecting with nature in surprising ways.

They’ve created this amazing space where everyone feels comfortable being themselves on the page.

I wholeheartedly recommend it.

Thank you for this blog. I hope to make it to a workshop before the month ends. My body tried to reset itself a couple of weeks ago so I’ve been focusing on resting and being even slower ❤️🤗🤗